One by one, absinthe was exiled from the bars of western nations.Ī Geneva-based satirical magazine, Guguss, printed a (now famous) poster to protest the ban in 1910, titled “The Death of the Green Fairy.” It shows a triumphant prohibitionist, dressed as a priest, trampling on the murdered Green Fairy. Switzerland was the first to outlaw absinthe, followed by Holland in 1910, the U.S. It was produced and exported here from the 18th century until 1910, when it was vilified, banned and bootlegged for nearly a century. Not so, it turns out! In fact, absinthe comes from the French region of Switzerland, in an area called Val-de-Travers, in the Swiss canton of Neuchâtel. And because of these associations, I had always assumed that the spirit originated in France. Absinthe was inextricably linked to illicit parties at the Moulin Rouge, or to the bohemian artists and writers of the Parisian golden age - James Joyce, Van Gogh, Hemingway, Picasso, Oscar Wilde, all noted consumers of la fée verte.

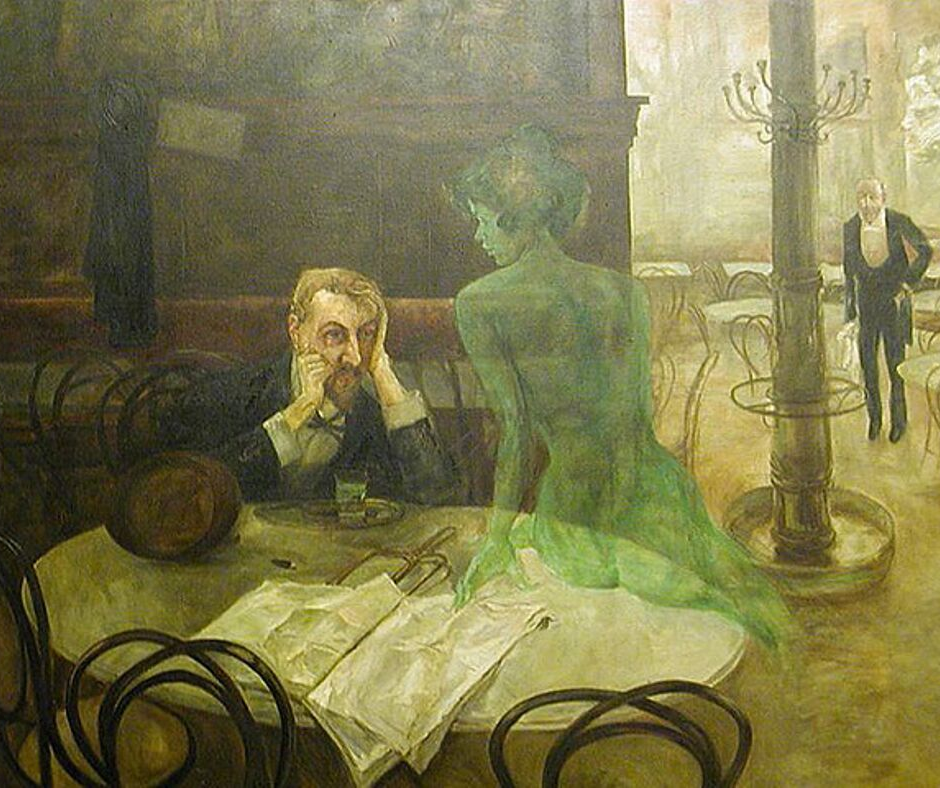

It instead remained in my mind’s eye, a fixture of La Belle Époque in 1920s Paris. But besides having a few flaming shots one wild night in Prague during my study abroad days, I had never actually tried to drink it properly. I have romanticized absinthe since the first time I watched Baz Luhrmann‘s Moulin Rouge in high school. And this means that above everything else, absinthe is sorely misunderstood. It’s a drink with a reputation, a bit of an edge, a wild side. Depending on who you asked in the early 20th century, it could be called la fée verte (the green fairy), or the Devil in the Green Bottle. It represents on one hand creativity and artistry, and on the other distortion, hallucination, and madness. It carries a air of mystery and a sense of lawlessness, the mere mention conjuring up scenes of dim-lit Parisian cafes, patrons with small glasses of a glowing green elixir.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)